by Rita Silverman, IRP Member

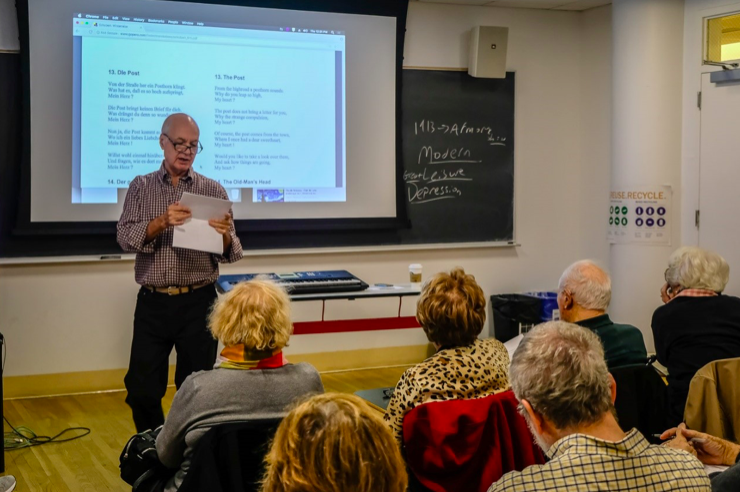

If visitors were to drop into an IRP study group, they might observe the following: the coordinator is perched on the table in the front of the room or sitting behind the desk or standing or walking around the front of the room. She asks a question of the group, and several hands go up. After she has called on someone, the participants listen to the speaker, and when he finishes, more hands go up.

At this point, the coordinator may do one of several things. She may call on someone else, and the discussion will proceed in that fashion. Or, she may push the responder a bit, asking for clarification or more detail. Or, before she calls on the next speaker, she may ask him, “Are you responding to the last comment or are you moving on?” Because this is a peer learning environment, the coordinator is encouraging a lively discussion, but that means more than just hearing one voice (or opinion) after another.

To delve more deeply into an idea, or to hear the divergent views in the room, and/or to possibly orchestrate an informal debate, the coordinator may slow the discussion down to make sure that all voices are being heard, or may challenge a comment herself, or look to the group to challenge what they hear. At other times, participants may be involved in peer learning by giving reports on an aspect of the topic under study that interests them, or they may work in small groups to examine a topic in more detail.

The visitor will notice that the interactions do not resemble those of a traditional college classroom; they are more like a graduate seminar. Peer learning offers IRP members an opportunity to learn from and to teach each another. Coordinators are not necessarily the experts on the content, but instead can be the “inspiration” to examine the topic, so that everyone in the room is both the teacher and the learner. Thus, IRP members use their life experiences (both professional and avocational) to develop study groups as well as to participate actively in study groups led by their peers.

While it is possible for a literature study group to be led by a retired professor of literature, it is as likely that a literature or history study group will be led by a retired lawyer, a poetry study group coordinated by a retired journalist, and a study group on politics co-coordinated by a retired psychologist and a retired publicist, who came together to develop a study group based on their shared interest in the topic but not by any professional expertise. And because the IRP is both a social and an academic setting, people who might never have met in their professional lives find others with similar interests while chatting over lunch, at a Friday wine and cheese get together, or at a membership social event. As well, they might have discovered a shared interest while participating in a study group discussion.

The informal structure of the IRP study groups and the practice of peer learning leads to some unexpected experiences. In a study group examining issues of American elections, one of the participants revealed that he had worked in the political campaigns of current candidates from their earliest forays into politics and was currently a “bundler” for a prominent presidential candidate. His insights and stories added a dimension to the study group that the coordinators hadn’t anticipated but eagerly welcomed and built into the syllabus.

Similarly, in a study group examining the life and career of Martha Gellhorn, during a discussion of the Spanish Civil War, a new member who did not expect to participate so early in her IRP career was a guest speaker, relating her father’s experiences in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

These shared learning activities occur because IRP participants are “ready to learn” and come to the study groups having read the assigned material (and/or watched the assigned video) and thought about the topic and assignment for that meeting. Often, participants find ancillary readings on their own and bring additional information to the class discussion. When participants contrast their learning experiences in the IRP with their earlier education experiences, they often comment on the fact that they have chosen to be in school.

While some members choose study groups on topics that they have an interest in, others report signing up for study groups in areas where they have no previous information or experience. A retired book editor, for instance, registered for the Cosmology study group because he had avoided science throughout his college and graduate school experience. One of the retired lawyers in the IRP loves taking literature study groups because after a career where she sought conclusions, literature discussions lead not to right answers but to more questions. Their motivation comes not from the desire for grades or credits, but from their own desire to learn.

It’s interesting to understand what brings retired people to the IRP and what keeps them involved. A 1994 examination found that while the members were a heterogeneous group, a desire for respect for themselves as learners and for some control over their learning experience was universal. IRP members reported the importance of stimulation and exposure to new ideas and their need to maintain mental acuity. They also reported the value of a social environment as part of the learning milieu—most people did not want to drop in for a class and leave. They appreciated the opportunity IRP to meet and interact with other people their age, the events that led to socialization beyond the classroom, and the respect with which this diverse group of learners treated one another’s ideas and learning styles.

The term “peer learning” describes the educational philosophy of the IRP. The theory supporting peer learning can be traced to John Dewey who wrote, “Education is not an affair of “telling’ and being told, but an active…process” (Experience and Education, 1938). Dewey’s Constructivist Theory proposed that experience is the foundation of knowledge, and the role of the teacher is not to “tell” but to create environments in which students actively engage in experiences that lead to meaningful learning. Lev Vygotsky, a Soviet psychologist, expanded on Dewey’s work, and his theories focus on the role of social interaction in cognitive development (The Mind in Society, 1978).

Malcolm Knowles has extended these and other learning theories into a theory of adult learning that he labeled andragogy (1994). Knowles developed five assumptions about adult learners that distinguish them from children as learners and should guide those who teach them. We can see each of these in practice in the IRP study groups:

- Self-concept—because of their more secure self-concept, adults can take part in directing their own learning. Examples include members who coordinate study groups outside of their areas of expertise and their willingness to participate in study groups that cover a wide range of topics.

- Past learning experiences—adults have a wide range of life experiences that support new learning. Most IRP members report that they were successful in their careers because they learned from their mistakes, because they were open to new diverse experiences, and because they could make connections between past experiences and new learning.

- Readiness to learn—adults as a group are more likely to see the value of new learning and therefore to focus on educational opportunities. Retired IRP members appreciate having the time to explore topics of interest that they could not have “dug into” during their professional lives.

- Different reasons to learn—typically, older adults return to educational environments by choice and without external pressures. Many members report that their career choices were determined not by their interests but by their need to earn a living once they finished school.

- Internal motivation—highly linked to 4. Older adults choose to learn for personal reasons, rather than for economic gain or as a response to pressure from others (parents, job supervisors, etc.).

The work of these three theorists (and many others) forms the tenets of peer learning, which can be observed at all age levels of learning. Maria Montessori applied the work of Dewey and Vygotsky to the education of young children. Cooperative learning theories are applied in elementary and secondary schools. Knowles’s work has been used in community colleges and programs for returning students and older adults seeking a new career path. We in the IRP have (sometimes inadvertently) put these theories into our teaching and learning experiences to the betterment of our community.