by Judith B. Meyerowitz, IRP Member

“We in the IRP represent a new venture for an institution of higher learning to accommodate the expanding educational demands of retired professionals…All of … [the New School’s] pioneering programs of the past and present will be publicized and subjected to public scrutiny, and the IRP will come in for its fair share of publicity. Perhaps other institutions of higher learning over the country may be motivated to start programs similar to ours.”

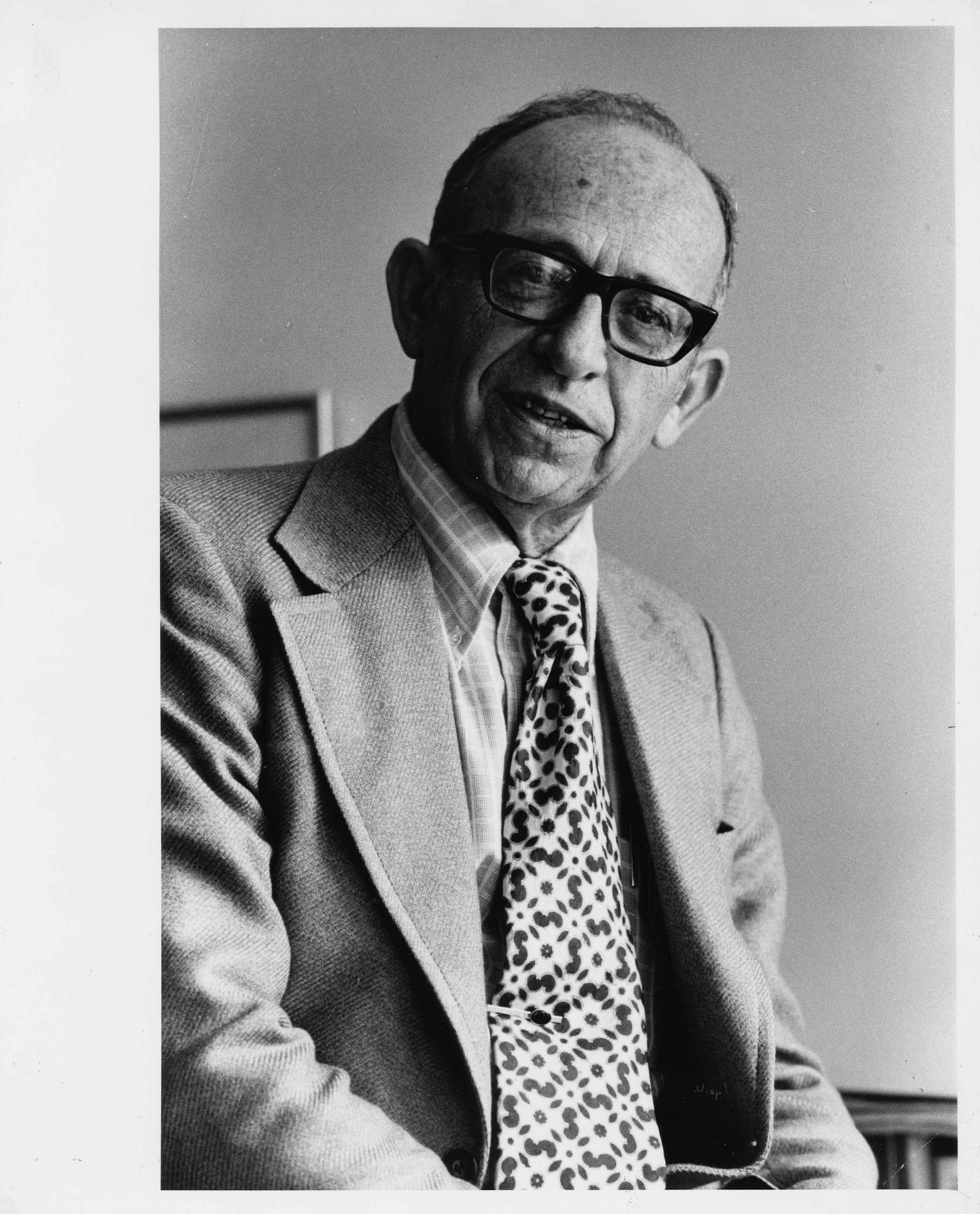

So Hy Hirsch, founder of the IRP reflected on the program’s importance in 1968 as the New School was approaching its 50th birthday. Now the centennial of the New School is an opportunity to look back at the origins of the IRP and how it has developed. (The histories on the 40th and 50th anniversaries by IRP member Walter Weglein have helped in documentation.)

The Vision

The year was 1962: we listened to the 21-year-old Bob Dylan’s debut album; we watched Wilt Chamberlain score an astonishing 100 points in a single professional basketball game and took a tour of The White House with a First Lady; we paid 28 cents a gallon for gas; we anxiously awaited the face-off between John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev over missiles in Cuba; we followed the news of John Glenn’s orbits of the earth and set our mission to put a man on the moon.

On Monday, Sept. 24, 1962, The Institute of Retired Professionals at the New School launched its own mission. In 2012 a local newspaper, the WestView News, noted, “At the time of its founding, the IRP was part of an early wave of empowerment movements among formerly overlooked groups.” The Sixties were not only revolutionary times for the young.

What was this “revolutionary idea”? Hy Hirsch, then a 58-year-old retired New York City social studies teacher and lawyer, observed “an oppressive boredom” among his retired teacher colleagues. They voiced a need to continue learning through taking courses but also to maintain their identities as teachers by leading courses. The opportunity arose when Hirsch had a “chance meeting” with Dr. Henry David, then president of the New School. Given its history of opening doors to other revolutionary programs and ideas, it was an ideal partnership. In fact, the name Institute of Retired Professionals came from President David. At the time, Senator Jacob Javits predicted that the “IRP will become a model for all universities to follow.” Now there are hundreds of similar programs across the country.

Growth of the IRP and Peer Learning

When school began that first September in 1962, 185 students enrolled, ranging in age from 55 to 85. “Most of them were as liberal in their thinking as the university to which they now belonged,” Weglein wrote. The annual fee of $35 entitled them to two courses a year at the New School.

Initially, Hirsch organized a Provisional Council of Members, and in 1965 he became the first director of the IRP when it became a permanent department of the New School. As quickly as that fall, the idea of coordinating a study group spread with a little “arm-twisting” from Hirsch. His first office was the school cafeteria. There he met with “business executives, a Parisian diamond merchant, a construction engineer, a pattern designer,” all of whom would become study group coordinators for the very first time while giving many teachers the opportunity to return to the classroom.

Numbers of both members and study groups skyrocketed in the first decades of the program. IRP membership eventually reached a peak of 1,000 applicants for over 600 places. The number of study groups grew from 30 a year to a peak of 80. Space shortages now limit the program to about 300 members and 36 study groups a semester.

Hirsch and the dean received letters from grateful members who wrote of the IRP “as a relief from the boredom of retirement that well-earned rest I am supposed to enjoy” or of being spared talking to other retirees “sitting on park benches whose conversation was limited to baseball, prices and the state of their health.” Another was thankful “for putting my mind to work and restoring my dignity.”

The first study group of the thousands given over the years was World Affairs. “As many as 200 members participated in the course, broken up into three separate sessions,” Weglein reported. “IRP groups were not meant to be ‘teacher-centered’ school courses. All courses would be participatory in nature, with the leader acting as moderator and the members learning from one another. This, noted Hirsch, was the beginning of peer learning for retired professionals.” Weglein compared it to John Dewey’s method of “learning by doing.”

After 17 years of leadership, in 1979, Hy Hirsch transferred the position of director to Henry Lipman, former associate dean and professor of adult education at NYU, who ran the program until 1988. He viewed peer learning as meeting not only the intellectual but the social needs of retirees as well: “One of the biggest problems with retirement is having to replace the social network that went with the job, walking in and being able to say you’ve just seen a Balanchine ballet, or are in the middle of a book. …When you retire you do not have that kind of contact,” he told the New York Times in 1986.

Over the years IRP members developed various programs outside of the classroom including informal talks, interest groups, and travel activities. Members have also expressed their creativity through submitting writing and photographs for the IRP’s Voices or participating in art exhibits.

One of Lipman’s roles was to escort guests from around the world on IRP tours. One member recalled several Japanese gentlemen asking where they could find “the silver group.” It finally occurred to someone that they were looking for the IRP!

Growing Pains and Change

In the early years there was no limit to the number of courses members could take, and they met every other week. Members were described as signing up for as many as 15 study groups and then “drifting in and out of classrooms.” This lessened the degree of preparation and involvement. Hirsch suggested setting up some special programs with greater rigor, but attempts to impose more structure from within the IRP or from the New School met with protest. The university urged adherence to its procedures such as weekly classes, following the semester calendar and formal registration.

Many members felt this impinged on the independence they desired. They saw themselves as a separate school not under the control of the university. A threat to the very survival of the IRP in the 1990s went to the heart of academic standards versus the idea of an open university with greater flexibility. Furthermore, these issues involved some of the key conflicts of retirement, itself, as a stage of life: structure versus freedom.

Additionally, the IRP was seen as needing new life. Over the years, members had brought in “like-minded” friends, resulting in a growing lack of diverse thinking and difficulty retaining new members. Ironically, as New York City was becoming increasingly diverse, IRP was “increasingly homogenized.” It was struggling to redefine itself, and that came at a cost.

Michael Markowitz, a former New School human resources director, was IRP director for almost 30 years, from 1988 to 2016, and led it through these critical times. In 1994, these issues came to the breaking point. The IRP refused to go along with requirements to comply with the rules of the larger university structure. Emotions ran very high.

“When the New School let it be known that IRP must conform to its standards—with weekly classes on a semester basis for which students would register—it would not be overstating the case to say that all hell broke loose,” Weglein quoted a new student as saying. “The cafeteria was filled with petitions, leaflets, signs posted—each designed to rouse the IRP membership to do battle with the New School.”

In an article in the New York Times, one member accused the university of trying to push out older people, while another expressed concern that she was losing her home. At the same time, the university appeared to be moving from its earlier focus on alternative education to a more traditional degree-granting undergraduate college.

The cost was the departure in December 1994, of more than 150 IRP members who formed a separate group. “Markowitz, working with the school administration and remaining members, tried to return the group to Hirsch’s vision of academic excellence and recreate the dynamic qualities of its early history but with a much more rigorous agenda than in those times,” Weglein wrote.

Looking to the Future

In its first 50 years, remarkably, the IRP had only three directors: Hirsch, Lipman, and Markowitz. During the search for a new director after Markowitz retired in 2016, IRP member Miriam Lawrence became interim director. In June 2017, Liz Weinmann was hired as director but resigned in December 2017. Currently the IRP is being led by members of the Executive Committee of the IRP Advisory Board, demonstrating that members of the community step forward to lead when required. They work with Adam Blaton, assistant director for administration, and Scott Amen, associate dean in the Executive Dean’s Office (EDO).

Meanwhile, the IRP remains committed to this founding ideal:

“One has only to spend a few hours in the company of this remarkable group to realize that the unused mind and the fading spirit are every bit as tragic as the dying body. New ideas, new subjects, new faces, prove to be more effective than the new wonder drugs or new vitamins…The strength and importance of this idea are reflected in the way branches are proliferating. There are people, more and more of them every day, who are saying no to oblivion.”

— IRP founder Hy Hirsch

IRP members at an early General Membership Meeting. IRP files.