by Student author from class on the History of The New School

It was towards the end of the Great War when the key events that led to the founding of the New School. In 1917, Nicholas Murray Butler, the president of Columbia University, dismissed Henry Dana and James McKeen Cattell due to their outspoken objection to the war. The former was an assistant professor in comparative literature and a socialist; the latter a distinguished tenured professor of psychology and a pacifist. This was not unusual during this time period. In 1917, Congress passed an Espionage Act that mandated sentences of up to 20 years for individuals who encouraged “disloyalty” in wartime. The dismissals of these two professors led to the resignation of Charles Austin Beard and James Harvey Robinson, both progressive historians. Robinson persuaded the first editor of the New Republic, Herbert Croly, to join them to found a “new school.”

Established in part to combat what Beard and Robinson had seen at Columbia, the New School was “created to oppose outrages against intellectual liberty, the institution sought to promote the study of human affairs in order to renovate democracy.”

They were blazing a new trail in adult education, a term that “had scarcely been coined and had generally taken to mean education for foreigners, lyceums, lectures, chatauquas, and the like.”

They believed that the social studies were a way to analyze the existing order of things as to allow for readjustments and social reform.

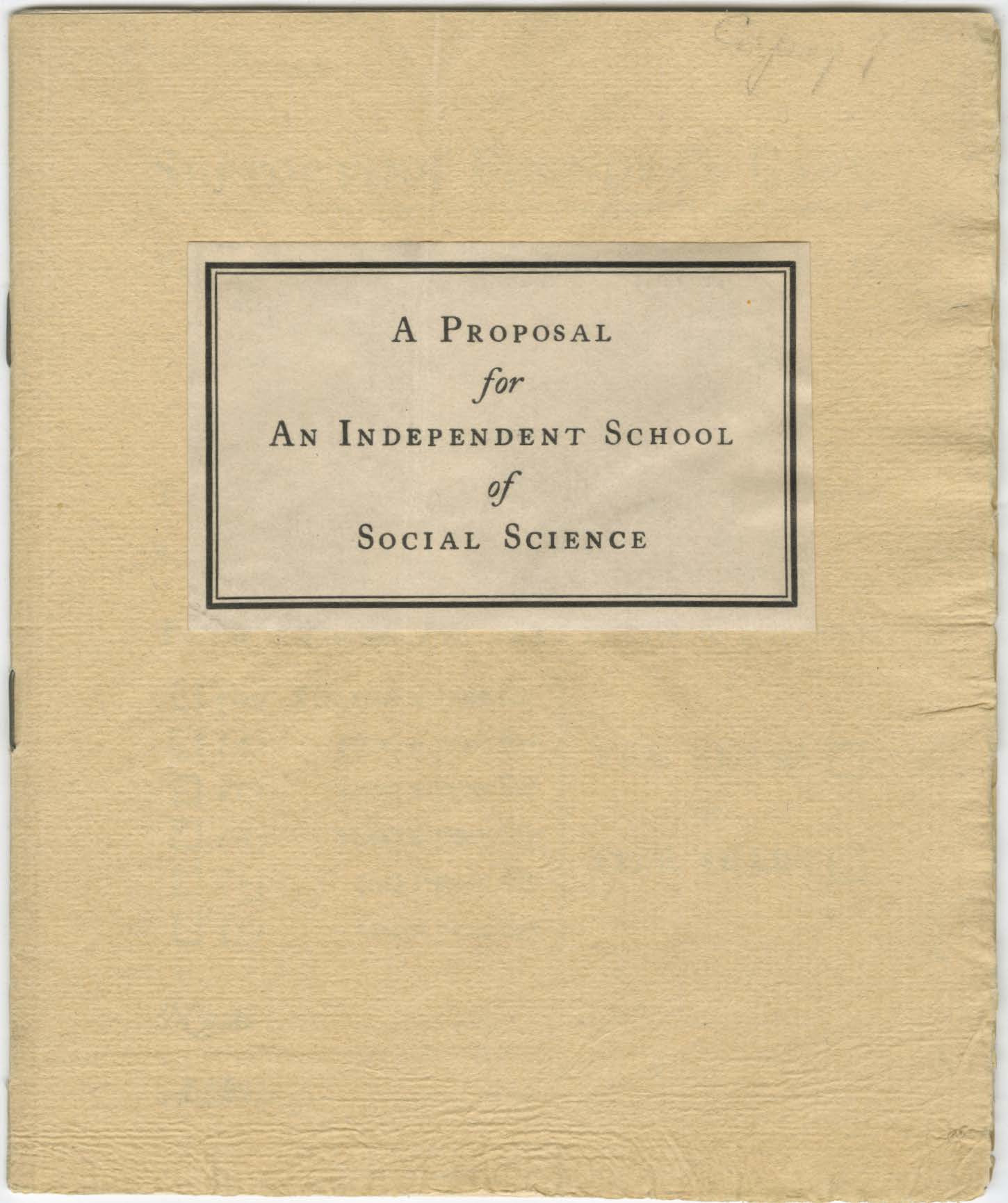

The 1919 “A Proposal for an Independent School of Social Science” argued that the circumstances over the past two and a half decades call for a “new type of leadership in every field of American life.”

The proposal suggests:

- revamping labor organizations;

- giving suffrage to women;

- efficiently teaching, through the scientific method and training in the field, future employees who will become an integral part of the country’s infrastructure.

Men and women should be able to question anything and talk amongst themselves about any topic they deem fit and should be educated on the current issues. For an institution to be successful at this, they must not be under the donors’ thumbs in which monetary stake overrides intellectual progress. According to Beard, “Endowment spells dry rot. Given an endowed income, a group of professors will sit in their cushioned chairs, avoiding all issues that might arouse controversy.” The instructors shall be given the freedom to investigate, publish, and teach and be relieved of administrative duties. They declared that most of the money coming to the school would be spent on research and education rather than administration.

The moment they opened their doors, the school became a topic of controversy. Some believed that aside from offering a “unique line of teaching” that the school was spreading pro-German and un-American propaganda. An article in The National Civic Federation Review (April 10, 1919) investigated who was involved in the school. It stated that Croly attempted to justify Germany’s war of aggression in his book The Promise of American Life. It quoted Theodore Roosevelt as saying that Robinson’s textbook Medieval and Modern Times is “an outrageous piece of German propaganda.” The Junior League also deemed the subject matter taught by the school too socialist and radical and declared that their members were too young to understand the content sufficiently.

The school had specialists in their field come and teach. There was Thorsten Veblen, the “heretical economist”; Wesley Clair Mitchell, the “pioneering student of business cycles”; Emily James Putnam, the “historian and leader in women’s education”; John Dewey, the “great philosopher of democracy and reform”; Horace Kallen, the “important student of ethnicity and cultural pluralism”; and many other progressives and pragmatists. The courses they taught went for $20.00 a course for each semester (which is $270.00 in 2013). They had open and closed courses: classes were either for the general public or for students who worked in the field or who the instructors thought had a special aptitude for the field. Classes were also held in the evenings so as to allow these who worked to be able to attend. There were 782 students in the founding year.