by Jen Larson

The Temple bell stops

But the sound keeps coming out of the flowers– Basho

Admittedly, this post is overdue, considering the fact I began working with the Kalil materials back in September 2010, and by now I have long since completed processing of this remarkable collection. But in all fairness, I had my hands full with the task at hand! Nevertheless, I would like to take a moment to present an overview of my appraisal and arrangement activities, and reflect on some of the challenges and surprises that I have encountered along the way.

Perhaps a small preface is in order here. The Kalil Collection contains a wide range of materials including personal papers (sketchbooks, student artwork, journals, correspondence and datebooks); professional papers (collegial correspondence, lecture and speech notes, research files, grant applications and awards); faculty papers pertaining to teaching appointments at both Parsons and UNC Greensboro (administrative documents, course materials, reference files, clippings, class plans, Masters Studio student exhibition materials); office records (administrative documents, clippings, promotional materials); project records (contracts, meeting minutes, photographs, slides, transparencies, sketches, drawings, photoprints), and original artworks and realia (craft and maquette materials for design objects). There is also an additional category of materials gathered posthumously by colleagues includes documentation of Kalil’s memorial service in 1991, administrative notes about the formation of the Michael Kalil Foundation and the Michael Kalil Endowment for Smart Design, exhibition materials for a “Designs for the 21st Century” (a 1993 retrospective of Kalil’s work, presented at Parsons), and a 1993 inventory document detailing the contents of Kalil’s office and home created by former Kalil Studio employee, Tom Garvey.

During the course of going through the boxes, not too surprisingly, I discovered that Kalil’s diverse body of materials retained only isolated pockets of organization and what appeared to be “original order.” Given this, I applied an overall arrangement scheme in order to apply folder-level intellectual control to this collection. Rehousing the papers was also a fairly straightforward set of tasks involving removing materials from decidedly non-archival plastic binders, sleeves and folders, and placing them into archival quality folders and document boxes.

However, Kalil’s plans, original drawings and sketches were another matter altogether! For anyone interested in his working methods, Kalil was visually oriented problem solver the act of putting pen and/or pencil to paper was absolutely central to his working method. His archive contains hundreds of drawings and sketches dating back to his days as a student continuing through to his professional practice and last collaborative project, “Rug for Threeing,” with Jean Gardner and Paul Ryan for V’Soske.

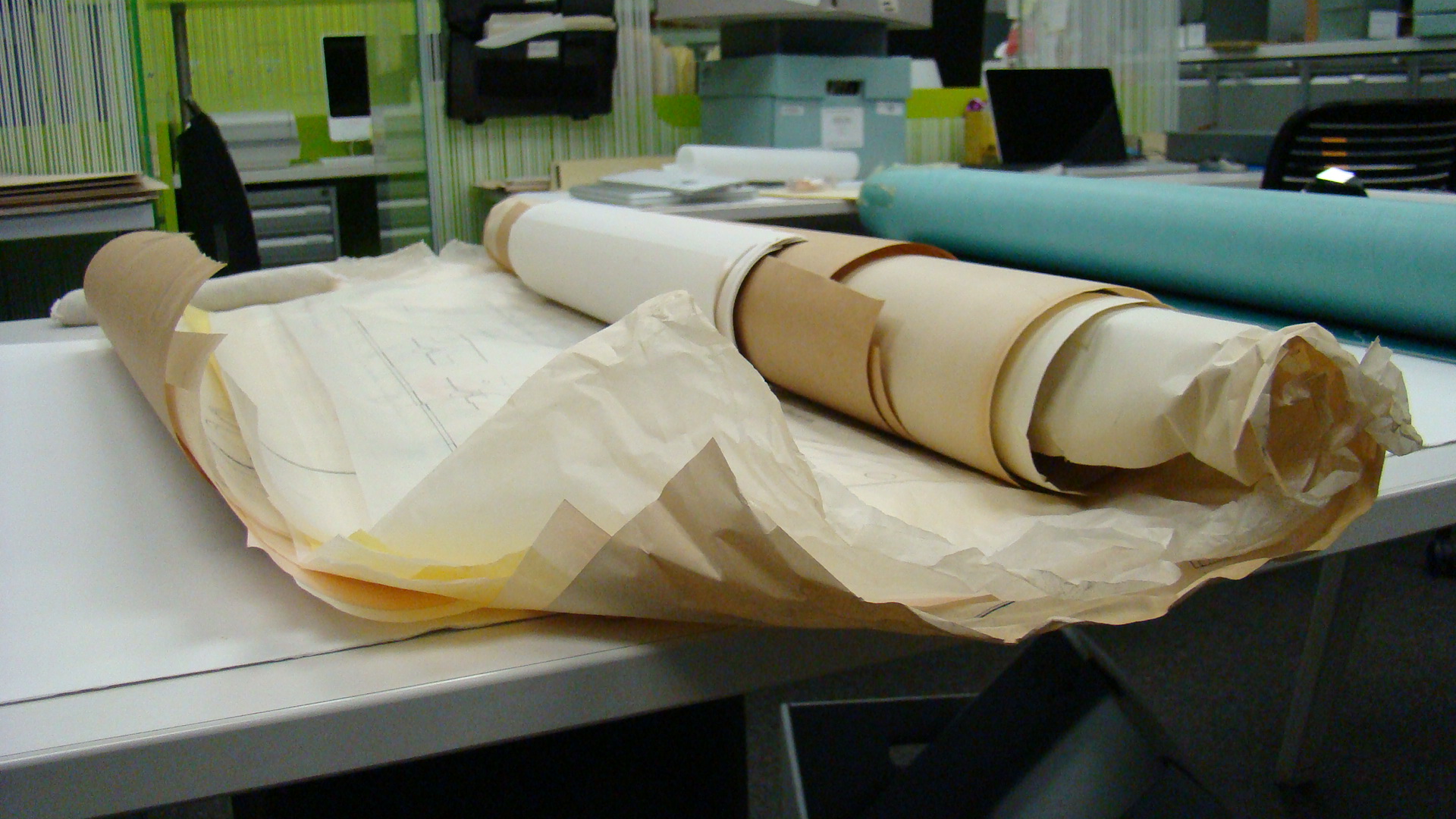

Most of Kalil’s visual materials are rendered on yellow or white tissue paper of varying sizes, but he drew in sketchbooks, on napkins, cardboard drink coasters, and in the margins of his notebooks and journals. There is also an long scroll of tan craft paper containing pen and pencil sketches—although I wasn’t able to determine which of his projects it pertained to, its a great illustration of a searching, ceaselessly creative mind at work. With the exception of a few smaller flat works, everything came to the archive rolled in cardboard tubes that were for the most part labeled with the project name. Throughout my processing of these materials, I jokingly referred to the process of removing and flattening these as like watching a clown car circus act—the drawings and sketches just kept on coming—a typical roll for any given project would unfurl to reveal a trove of smaller sketches. I would separate these and sort them by size and media, and do my best to flatten and folder these groups/sub-groups in such a way that wouldn’t be completely inconvenient for a researcher to open and sift through. This may have been the most labor intensive and delicate aspect of processing Kalil’s collection.

I chose the Basho quote to begin this post because I feel that it’s an apt statement in regards to the power of action- in this case, the vibrancy and immediacy of Kalil’s hand and intellect that is so present throughout the entirety of his materials-and also the potential of these materials to “speak” to researchers about 20th century design history long after Kalil’s direct involvement with them. Metaphorically speaking, my job as an archivist has been to be a steward of this garden, and make sure that clear paths are made for future scholars to find the flowers.

Image

New School Archives and Special Collections https://digital.archives.newschool.edu/index.php/Detail/objects/KA0119_…