by Carol Wilder and Peter Haratonik

Film studies and making at The New School are a match made in centennial history. The first U.S. university course in film history and criticism was offered at The New School in 1926 by producer, writer and editor Terry Ramsaye. A course in screenwriting – “Photoplay Composition”- had been offered at Columbia since 1915, but Ramsaye’s sweeping survey was the first to suggest film studies as an academic pursuit. Ramsaye’s 869 page tome, A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture through 1925, was published the same year he offered his New School class. Each copy of the first edition was signed by Thomas Edison, who wrote in the preface “This is, I believe, the first endeavor to set down the whole and true story of the motion picture.”

Motion pictures had many innovators in the latter half of the 19th century. With photography an established medium by the Civil War, there was a frenzy of inventiveness working to establish moving pictures, creating contraptions like the Stroboscope, Zoetrope, Praxinoscope, and Zoopraxiscope. In the race to claim inventor status, it was George Eastman who first made the film (1885), Thomas Edison who introduced the motion picture camera (1891), and Auguste and Louis Lumiere who put it together with a projector in 1895, the year generally observed as the birth of the movies.

Edison the prolific inventor lost the “invention of film” designation because his Kinetoscope only accommodated one viewer at a time, while the Lumiere brothers could project a shared experience to an audience, a defining feature of the movie medium. It is rumored that the Lumiere’s Arrival of a Train (1896) sent audience members fleeing in panic. However apocryphal the tale, it evokes the power of cinema as a strange and intoxicating new medium – the virtual reality of its day.

The years 1926-27 were a pivotal time. While some major productions like Birth of a Nation (1915) had been released in the previous decade, the first Academy Awards were not held until 1927. That same year the first synchronized sound film – “the talkies!” – was released – The Jazz Singer. It was not until 1930 that All Quiet on the Western Front won the first Best Picture Oscar for a sync-sound feature.

This context set the radically innovative stage for Ramsaye’s 1926 “History of Motion Pictures” New School course, which generated more than a dozen pieces of far flung press coverage in the NY Herald Tribune, New York City World, New York Telegram, Wilkes-Barre PA Leader, Baltimore Evening Sun, Wildwood New Jersey Leader, Johnstown PA Tribune, Boston Christian Science Monitor, and Seattle Washington Times. Many of these notices led with the sentence “At last, the movies have been recognized as worthy of a place in higher education,” confirming the originality of Ramsaye’s course and the visionary venue of The New School.

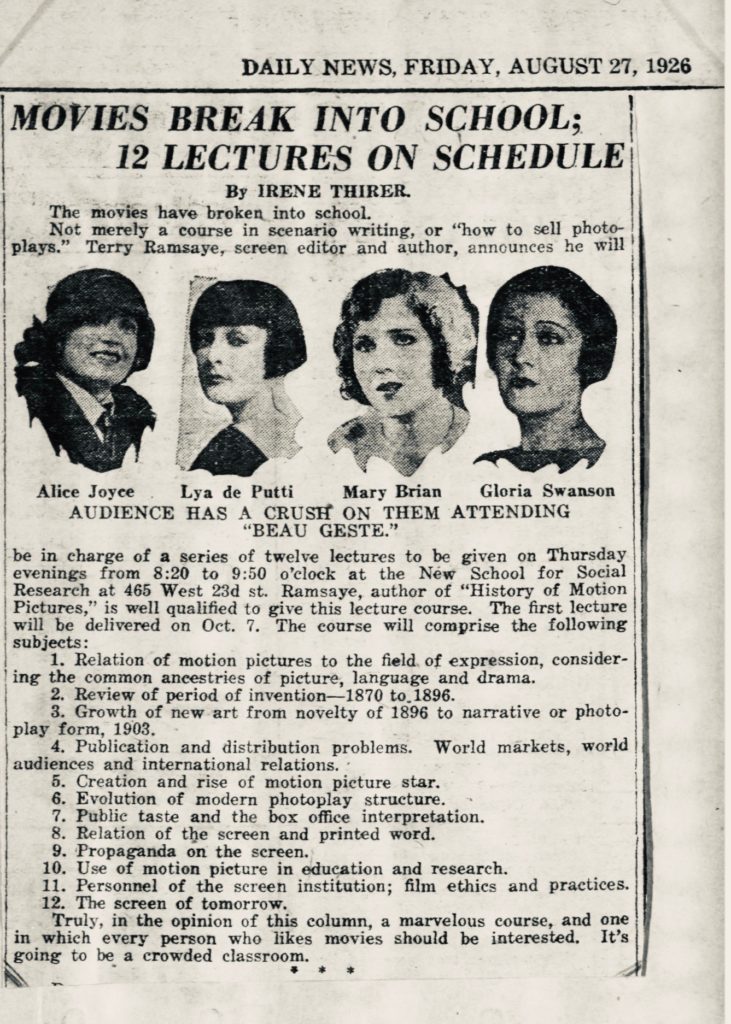

On Friday, August 27, 1926, New York Daily News reporter Irene Thirer announced “Movies Break Into School; 12 Lectures on Schedule.”

Thirer writes that this is “not merely a course on scenario writing,” perhaps to distinguish it from Colombia’s screenwriting courses, and lists a remarkably comprehensive list of topics including history, distribution, stardom (with accompanying fetching leading lady photos), screenplay structure, screen vs print, propaganda, and film ethics and practices.

Dana Polan’s 2007 history of US film education Scenes of Instruction includes a chapter about Ramsaye. Polan thinks little of Ramsaye’s academic rigor, but acknowledges his historic contribution. Ramsaye was involved with The New School until about 1930, when his correspondence with Alvin Johnson and others documents Ramsaye’s disillusionment when he was unable to round-up film luminaries to participate in his lecture series. Polan thinks more highly of a 1932 course “Lands, Films and Critics,” taught by Marxist critic Henry Alan Potemkin, whose tenure was cut short when he died suddenly at age 33. With Potemkin’s death, Film Studies at The New School died, too, for the next decade.

II.

Throughout much of its 100-year history, New School students were predominantly non-credit “Adult Ed,” seeking enrichment, enlightenment and community as the founders had initially intended. Mention The New School to any New Yorker living in the city from the 1940s through the 1970s and they will have a story about a course they took or lectures they attended or a lifelong friend they met. Anatole Broyard captures this feeling in his sensuous Kafka Was the Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir:

Like the village itself, The New School was at its best in 1946 After a war, civilization feels like a luxury and people went to The New School the way you go to a party, almost like going abroad. Education was chic and sexy in those days. It was not yet open to the public. The people in the lobby of The New School were excited, expectant, dressed to the teeth They struck poses, examined one another with approval. They had a blind date with culture and anything could happen.

By the 1970’s The New School continued to be the place to “study your passions.” A wide variety of lecture series became a New School hallmark. Thousands came each semester to hear noted lecturers like social critic Max Lerner. Film series became among the school’s most popular events. Film historian Willam K. Everson filled the auditorium on Friday evenings with screenings of his personal cache of films. Leonard Maltin’s animation history course was a perennial crowd pleaser and was among the first to take this art form seriously. Toby Talbot, the doyenne of the New York independent film scene, was an inspiration to many. The faculty’s love of film was infectious and The New School became a second home for cinephiles.

In 1972 the Cinematic Arts and Television Department widened its scope. With a new building and The New School’s merger with Parsons, film production, screening and writing classes began to grow. Donald Spoto launched his influential course on Alfred Hitchcock. Richard Brown’s “Filmmakers on Film” course, which began in 1972, gave rise to a gamut of celebrity-driven courses. Brown was hugely successful and was a forerunner of James Lipton’s hit Bravo series “Inside the Actors Studio”

The New School also offered the first courses in the media business with film accounting taught by Sam Goodrich, film law by a founder The Lincoln Center Film Society. In the early 1970s The New School opened its first 16mm film production facilities in 66 Fifth Ave while continuing to offer other production classes at outside studios.

While most students registered on a non-credit basis, many students found that they could also create a “major” as part of the school’s groundbreaking adult BA Program. By the late 1970s Film Certificate options were also available, becoming the incubator of hundreds of progressive and experimental independent films.

In 1975 The Center for Understanding Media, founded by noted film educator John Culkin, merged its graduate courses with the New School. John Culkin became the founding director of the first U.S. Master of Arts in Media Studies Program.

In 1978 Peter Haratonik, one of the MA’s founding faculty, was named Director of the MA Program and Chair of The Cinematic Arts and Television Department. For the first time, all media courses were under the umbrella at The New School. today recognized as The School of Media Studies.

The mid-1980s were the last hurrah for big screening series, thanks to the introduction of the VCR that allowed viewers for the first time to screen movies in their living room. Film series offered in the Summer of 1985 included Donald Spoto’s famed Hitchcock course “The Furious Vision,” screening Notorious, Strangers on a Train, Rear Window and nine other films; William Everson’s course marking his 50th series celebrating a spectacular lineup of “lost, forgotten and overlooked films”; Sybil del Gaudio’s “Design and Style in the Cinema,” with ten films from Grand Illusion to Johnny Guitar; and Deirdre Boyle’s “Documentary Film: Its Art, History and Future,” including Nanook of the North, Triumph of the Will, Battle of Britain and Primary. Only Boyle’s course still thrives 35 years later, and it is now a degree course not a non-credit offering of the sort that attracted so many large rapt audiences. In yet another example of unforeseen and unintended consequences of technology, the days of the big movie screening series had succumbed to the home video revolution.

III.

Broyard was not the only author to write about The New School of this iconic period. Auntie Mame, the flamboyant character invented by Patrick Dennis in 1955, went to The New School “so that I can be of some intellectual stimulation to your little ones.” Pete Hammill wrote in Forever: A Novel (2002) “ . .In September he saw her again at last, coming out of The New School on Fifth Avenue cutting across 14th street to the North side of the street then moving West, like a detective on the trail of a murder suspect. . .”

In 2004 Carol Wilder produced an eclectic video of The New School in popular culture that shows clips from everything like Seinfeld, Will & Grace, and Friends to Law and Order and The World According to Garp. In all mentions like this, including a line by John Travolta’s girlfriend in Saturday Night Fever, The New School is used as a trope for hipness. As The New School attracted more degree students in the 1990s and left the adult education population to institutions like the 92ndSt Y or to their own media-saturated living rooms, the image of hipness faded while progressive values continued to prevail within the degree-oriented classrooms.

The introduction of portable video equipment – the “Portapack” – in the 1970s had substantially lowered the barrier to entry for moviemaking and spawned a surge of independent work. While filmmaking at its easiest is very hard, accessible technology greatly democratized the medium. Many New School film faculty participated in early independent filmmaking, including Alan Berliner, the late writer, artist and experimental filmmaker Paul Ryan, and the documentary film scholar Deirdre Boyle.

But just as film had transformed the first half of the 20th century and television was the first defining medium of the second half, little did anyone know what was about to come just a few decades later when the digital revolution slipped in on little cat feet.

IV.

Almost no one clearly saw the emergent scope of the digital revolution on the horizon. Post WWII government funding for engineering in general and computer science in particular ushered in the digital age that has left no corner of life untouched. Wilder sketched the broad strokes of this in 1997’s Being Analog, at a time when she was fully involved in The New School film program’s conversation about how, when and why to make the analog to digital transition in equipment and pedagogy.

It was a heated debate from Hollywood to Greenwich Village. Filmmakers for the most part resisted digital video, mostly for reasons of (since improved) image quality. The arguments ran deep. Several minutes into a conversation with a film person about the relative merits of analog film versus digital video you were likely to find yourself in an almost mystical realm. The chemical/organic/ mechanical properties of film captivated its users like no other medium. Film was described as rich, tonal, deep, warm, sensual, alive. Digital images were flat, bright, sharp, hard, formal, cold sterile. Even if pixel-based and crystal-based images were equally “good,” they were not the “same.” Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer and former New School Film faculty member David Turnley said at the time that “the irregular shape and arrangement of the silver halide crystals themselves, which were literally spray-painted in layers on the film stock, create a richer and more complex texture than the identical number of square pixels can do regardless of their density.”

Try arguing with that.

But fast forward to 2019 and your five-year-old can now make a movie on your phone, though you can be pretty sure it won’t be any good. Pedagogically, it is important to remember that there is a highly evolved grammar of film and a great repertoire of its art and craft. It is rocket science in a box with light as its jet fuel.

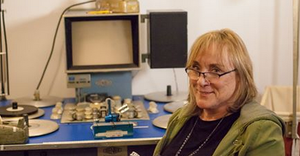

Filmmakers were traditionally also incredibly attached to their Steenbeck flatbed analog editing machines. Witness Wilder at her beloved flatbed – a machine that lets you feel, see, manipulate, hang in strips, the actual image itself, and where a cut is actually a cut that can make you bleed, not a razor blade icon on a computer screen. The kinesthetic pleasure is intense and the aesthetic outcome is personal and organic.

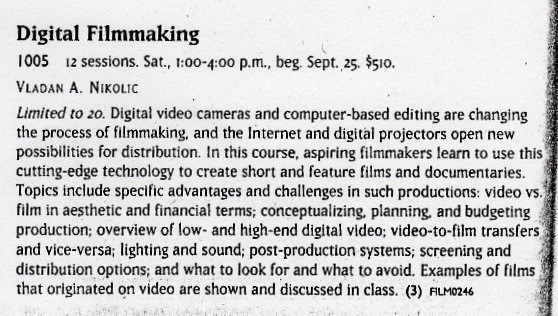

Alas, the digital corner was turned when The New School offered its first digital editing class in the summer of 1996, taught on a borrowed AVID at a nearby commercial editing facility.

Within three years the Media Studies graduate program was offering almost twenty digital editing classes, while for the most part film (not video) cameras were still in use. By 2018 film classes enrolled more than 600 students from four divisions of the University. Beginning film students are still required to acquaint themselves with 16mm analog technology.

Over the years multiple attempts to collaborate deeply with Parsons and/or develop a film MFA have gained little traction. Even so, between the 50 year old film certificate program (a downtown NYC independent film legend), Media Studies M.A. graduate students, and now undergraduates as well, New School film students produce 75-100 films each year. The best are screened at Fine Cuts: The New School Invitational Film Show, produced by two-time Emmy-winning faculty member Rafael Parra and celebrating its 40th year in 2019. Student films are also screened in festivals worldwide and have garnered numerous awards including Student Academy Awards for Jordan Waid’s The Piece and Tal Shamir’s The Vermeers among others and an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 2012 for alumna Laura Poitras’ Citizen Four.

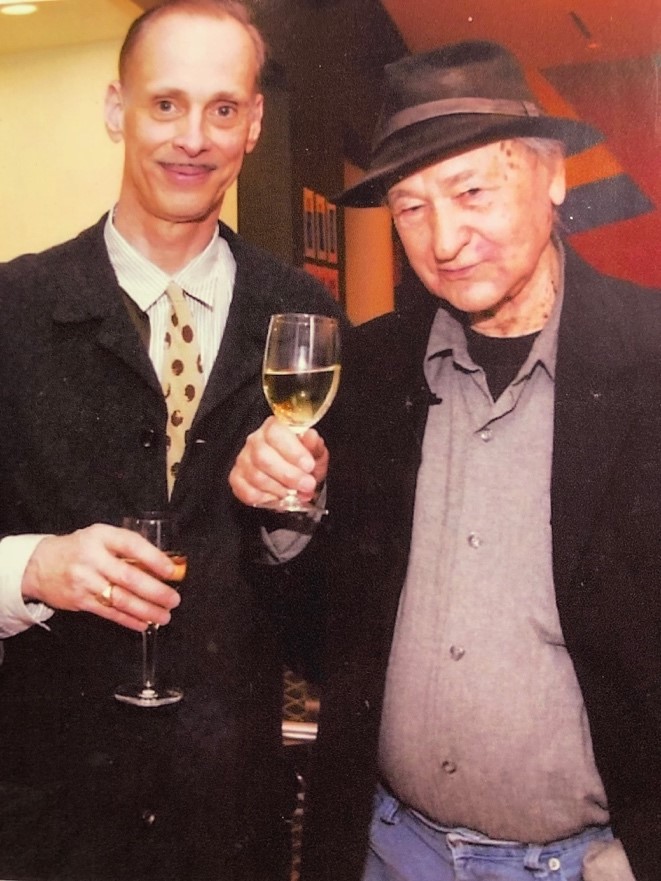

In 2003 a generous endowment from New School trustee Dorothy Hirshon inspired the creation of the annual Hirshon Film Award, that has since honored DA Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, John Waters, Laurie Anderson, Peter Davis, John Cameron Mitchell (Hedwig!), and others. The 2019 recipient is Raoul Peck, Academy Award nominee and director of I Am Not Your Negro (2016).

Having negotiated the digital revolution with some success, Hollywood now has another related monster challenge on its hands – distribution. Film no longer has to be distributed by mail in costly heavy cans. Bits weigh virtually nothing and can be transmitted electronically. This has been increasingly the case for more than a decade, but the fact that in 2019 the “streamer” film Roma – a derisive term for a film released online – lost the Academy Award Best Picture prize by only a hair has film executives apoplectic. Roma had the bare minimum theatrical release to qualify for the Oscar, but is essentially a Netflix movie, giving fits to the long prevailing business model of theatrical distribution. Media heavyweights like Barry Diller and Steven Soderbergh have thoughtfully weighed in on this most recent disruption and its implications for the art and business of film. Media Studies Dean Vladan Nikolic has offered his enlightened thinking in a 2017 book Independent Filmmaking and Digital Convergence.

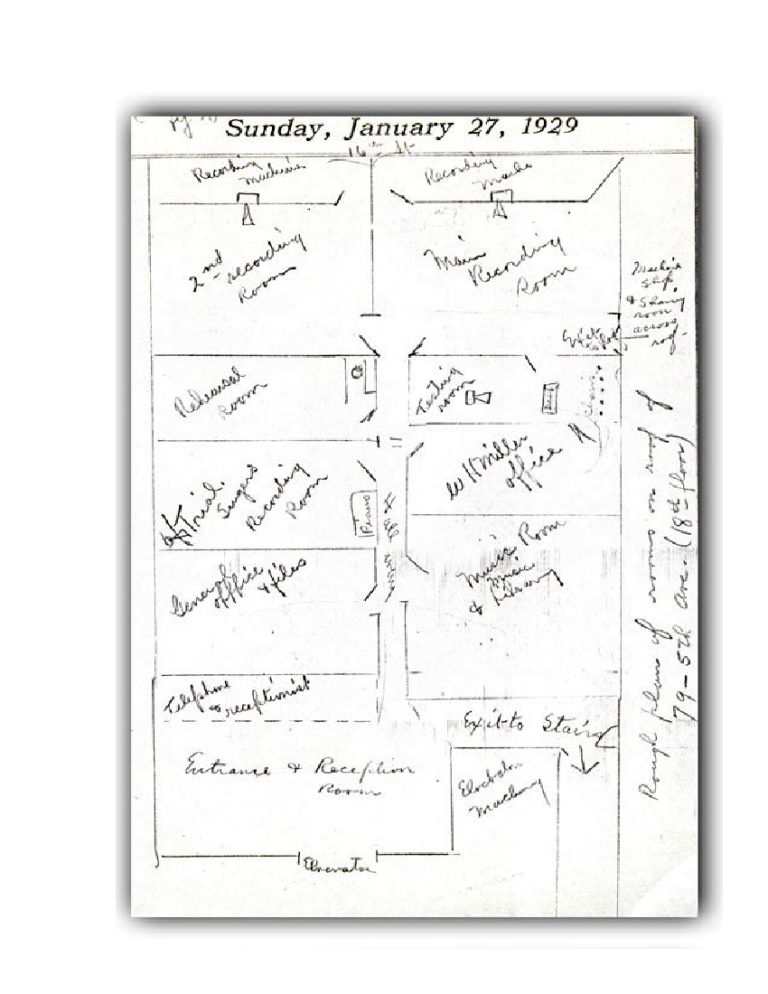

It’s complicated, to say the least. But as long as The New School teaches storytelling across a range of media platforms current and emergent, the next one hundred years will meet the challenge. Thomas Edison is a small world case in point. His 1929 New York studio on the 18th floor of the historic Knickerbocker Building at 79 Fifth Avenue is just two floors above today’s Media Studies and Film office. Colleague Barry Salmon even found the original floor plan.

Edison may have been passed over for the film inventor title by a wrinkle in history, but his independent spirit, intuition and resilience made its mark and provides an inspirational lodestar for the future of moving picture magic.

Carol Wilder and Peter Haratonik have a combined 28 years leading Media Studies and Film between 1976 and 2017 as Director, Chair, and Dean. They thank Wendy Scheir and Jenny Swadosh of The New School Archives for their generous assistance.